A Sensory Experience That Two or More Persons Can Experience Objectively Is Known as:

Abstract

Sensory experience rating (SER) is a recently adult subjective lexical index that reflects the extent to which a discussion evokes a sensory and/or perceptual experience in a reader (Juhasz & Yap, 2013; Juhasz, Yap, Dicke, Taylor, & Gullick, 2011). In the present study, SERs for a gear up of v,500 Spanish words were collected, which makes this the largest ready of norms for SER in the Spanish linguistic communication to date. Additionally, with the aim of further exploring the implications of this new indicator and its relations with other psycholinguistic variables, a variety of correlational and regression analyses are provided. The results showed that SERs significantly correlated with imageability, age of acquisition, and a number of variables related to perception and emotion. In addition, SERs predicted a significant amount of variance in lexical conclusion times when other variables were controlled.

Normative studies constitute highly valuable resources for researchers from dissimilar domains in cerebral science, since they let for both manipulation and control in the design of experiments. In addition, these studies often give ascent to new knowledge, thereby contributing to the enrichment of theoretical evolution in psychology. In the last decades, a large number of normative studies take been made available for several languages, mostly for English (come across Proctor & Vu, 1999, for a review; see as well Vaughan, 2004), only too for other languages, such as Spanish (for a review, run into Pérez, Campoy, & Navalón, 2001), French (e.m., Bonin et al., 2003), Italian (eastward.g., Barca, Burani, & Arduino, 2002), and Chinese (e.m., Liu, Shu, & Li, 2007). Normative data take been nerveless for a variety of stimuli, among which verbal materials, and specially words, predominate over others. Also, numerous psycholinguistic variables, both objective (east.grand., number of letters/syllables, discussion frequency, orthographic, and phonological structure) and subjective (e.g., familiarity, imageability, concreteness, melancholia values, age of conquering), have been carefully studied. As a result, an extensive corpus of word ratings is available today, which constitutes a major advantage for researchers.

In recent times, new theoretical points of view in cognitive psychology have led to growing interest in new variables. In this sense, a remarkable perspective in psychology, which has aroused corking interest amidst researchers, is the grounded knowledge theoretical framework, which holds that noesis is determined, in multiple ways, past modality-specific simulations, bodily states, and situated activeness, within a physical and social context (Barsalou, 2008). Thus, all psychological processes and mental activities would be influenced in a significant way by sensorimotor systems, emotions, and the body itself (Glenberg, 2011). For example, recent studies suggest that language comprehension implies constructing sensorimotor simulations of the situations and events described in sentences. According to this perspective, those simulations involve the activation of the encephalon's systems of perception, action, and emotion, the same ones that are activated in a real situation (Glenberg, 2011; Glenberg & Kaschak, 2002; Kaschak et al., 2005). In a like vein, conceptual representations, and therefore our knowledge about the globe, have been argued to exist grounded in modality-specific systems (Barsalou, Simmons, Barbey, & Wilson, 2003; Kiefer & Barsalou, 2013). More than specifically, Barsalou (1999) suggested that perceptual states that emerge from sensorimotor systems are stored in long-term memory and can operate as symbols that are modal and analogical in nature.

Due to the considerable interest that this approach has elicited among a good number of researchers, and owing to the importance that sensory systems certainly have for understanding human cognition, it becomes necessary to collect information about sensory properties of concepts, as completely and rigorously every bit possible. This will let researchers to conduct further investigation with carefully selected materials and with appropriate control of variables. In this context, Juhasz, Yap, Dicke, Taylor, and Gullick (2011; see likewise Juhasz & Yap, 2013) were first to present a new variable called sensory experience rating (SER), which reflects the extent to which a word evokes a sensory and/or perceptual feel in the reader. Equally Juhasz et al. (2011) stated in the original instructions of the task, this sensory experience implies an actual sensation (taste, touch, sight, sound, or smell) that is experienced when a certain give-and-take is read. Information technology is noticeable that the SER alphabetize is not referred to a unmarried sensorial modality, merely it examines all sensations at one time. In that respect, SER is different from other indexes that accept focused on individual sensorial modalities. For instance, Lynott and Connell (2013) provided modality-specific norms for 400 nouns, including ratings for each of the five sensorial modalities (i.east., auditory, gustatory, haptic, olfactory, and visual). Similarly, Medler, Arnoldussen, Binder, and Seidenberg (2005) nerveless ratings in iv sensorimotor domains (sound, color, manipulation, and motion), as well as emotion ratings, for 1,402 English words. And McRae, Cree, Seidenberg, and McNorgan (2005) collected semantic characteristic production norms for 541 living (e.g., dog) and nonliving (east.g., chair) concepts, which were and so grouped into ix cognition types, amidst which the v sensorial modalities are included. Furthermore, Amsel, Urbach, and Kutas (2012) provided ratings for a fix of 559 object concepts on 7 different perceptual and motor attributes (color, motion, sound, odor, gustatory modality, graspability, and pain). Interestingly, these norms include some attributes that, to engagement, have received little attention in conceptual processing studies, such as smell intensity or likelihood of pain. Another variable that addresses the importance of sensorimotor representations in cognition is the body–object interaction (BOI) index, which reflects the ease with which individuals tin physically interact with a word'due south referent using whatever part of their trunk (Bennett, Burnett, Siakaluk, & Pexman, 2011; Tillotson, Siakaluk, & Pexman, 2008). SER, as an integrative measure of the sensory activation that concepts evoke, should encapsulate all private sensorial modalities and should correlate with dissimilar subjective variables that tap perception, activity and emotion in unlike ways. In this vein, one of the main purposes of the present study is precisely to explore these relations.

Furthermore, recent studies have explored how SER is related to semantic or lexical psycholinguistic variables likewise as to performance measures of give-and-take recognition. Thus, the near remarkable correlations accept been reported between SER and imageability and age of conquering (AoA), indicating that words with higher SERs are more probable to be more imageable and to have an earlier AoA in comparison with low-SER words (Bonin, Méot, Ferrand, & Bugaïska, 2015; Juhasz, Lai, & Woodcock, 2015; Juhasz & Yap, 2013; Juhasz et al., 2011). Too, a recent study by Bonin, Méot, and Bugaiska (2018) has institute a positive correlation between concreteness and SER ratings, indicating that words with higher SERs tend to be more concrete. These researchers contend that, similarly to high-SER words, the representation of concrete words might be mainly based on sensory–perceptual information (see also Kousta, Vigliocco, Vinson, Andrews, & Del Campo, 2011). However, despite the mentioned correlations, SER has been argued to take a unique character as a semantic variable. For example, Juhasz et al. (2011) reported a multiple regression assay with SER as the dependent variable, in which a full of x established word recognition variables just predicted 29.4% of the variance in SER. Moreover, and chiefly, SERs have proved to reliably predict lexical decision response times (Bonin et al., 2015; Juhasz et al., 2015; Juhasz & Yap, 2013; Juhasz et al., 2011; Kuperman, 2013) when other psycholinguistic variables are controlled, suggesting that it plays a significant part in conceptual lexical–semantic processing, particularly when sensory and perceptual features of concepts are taken into account.

Given the growing involvement in this new variable and its potential importance for several research aims in cerebral psychology, SERs started to be nerveless in languages other than English. For example, Bonin et al. (2015) recently obtained SERs for ane,659 French words. In Castilian, Hinojosa, Rincón-Pérez, et al. (2016b) collected SERs for the 875 words included in the Madrid Affective Database for Castilian (MADS; Hinojosa, Martínez-García, et al., 2016a), including verbs, nouns and adjectives. To the best of our noesis, this is the only normative SER written report in Spanish.

With the aim of further contributing to this growing trunk of information, the present study's primary objective was to provide SERs for a fix of 5,500 Spanish words. Importantly, the target words were selected from previous studies collecting Spanish norms for other relevant psycholinguistic variables, so that researchers using verbal stimuli in Spanish can make use of a rich and well-described pool of words for experimental purposes. A second objective was to analyze the relationships between SER and other well-established psycholinguistic objective and subjective indexes, in social club to farther explore and depict the implications of this variable for information processing. AoA, frequency and imageability are of particular interest hither, equally these variables take been found to correlate with the SER. Also, because it is argued that SER is a unique semantic variable that encloses diverse individual sensorial modalities that underpin perception, action, and emotion, the relationship between SER and different subjective psycholinguistic variables associated with those three dimensions will exist examined. And finally, as it was done in previous studies in English language and French, the predictive value of the SER on Spanish language lexical conclusion times and discussion naming will exist assessed.

Method

Participants

A total of 420 undergraduate students of the Universities of Salamanca, Valladolid, and La Laguna, all located in Spain, participated in the study in commutation for course credit. All data from 29 participants were discarded due to inadequate performance in the rating job, applying at least one of two criteria: twenty or more trials in a row with the same response, or 50 or more responses made in less than one second. Thus, the final sample included 391 participants (333 female, 58 male), all native speakers of Spanish, with a mean age of 19.7 years (SD = 3.23; range = 16–58 years).

Stimuli

The ready of words to exist normed was constructed by obtaining stimuli from existing lexical databases in Spanish, with the aim of assembling a pool of words for which other norms of psycholinguistic involvement were currently available. Specifically, the ready was formed to include (a) two,765 mono- and multisyllabic words with known lexical-decision and word-naming times (Davies, Barbón, & Cuetos, 2013; González-Nosti, Barbón, Rodríguez-Ferreiro, & Cuetos, 2014); (b) 1,512 words with known affective norms (Redondo, Fraga, Comesaña, & Perea, 2005; Redondo, Fraga, Padrón, & Comesaña, 2007); (c) 750 words with known BOI norms (Alonso, Díez, Díez-Álamo, & Fernandez, 2018); (d) 238 1-discussion names denoting Snodgrass and Vanderwart'southward (1980) drawings (Fernandez, Díez, Alonso, & Beato, 2004; Sanfeliu & Fernandez, 1996); (e) the 1,109 adjectives with known AoA norms from Alonso, Fernandez, and Díez (2015); and (f) a subset of 1,024 verbs with known AoA norms from Alonso, Díez, and Fernandez (2016), representing the consummate range of AoA (from 3 to xv). We also added half dozen other nouns respective to months and days of the week, in order to consummate those categories. Once redundant entries were eliminated, the final set was equanimous of a total of 5,500 Spanish words of varied length, frequency, and part-of-speech category (i.due east., grammatical category).

Procedure

The 5,500 stimuli were randomly divided into 11 questionnaires, which were administered using Online Ratings of Visual Stimuli (OR-Vis), an open-source software tool (Hirschfeld, Bien, de Vries, Lüttmann, & Schwall, 2010) adult to conduct rating studies. Each questionnaire contained 500 different words, as well as 23 repeated words, selected randomly from among the words within each questionnaire, that would allow for a subsequent intrasubject reliability test. Each target word was rated by an average of 35 participants, with a minimum of 33 valid observations for each word.

The task was performed in groups of xv to 25 participants at a time, using individual computers in a large computer room. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the questionnaires, with the only brake that a similar proportion of male and female participants' responses were recorded beyond questionnaires. Participants were required to rate the 523 target words, which were randomly presented. In each trial, a target word was presented in the center of a computer screen and a 7-point rating scale was displayed below, with verbal labels at both extremes indicating the calibration values. Participants had to rate the degree of sensory experience that each word evoked for them past selecting a single number on the scale, via mouse click. Participants were asked to answer rapidly, only as accurately as possible.

The rating instructions were taken from Juhasz et al.'southward (2011) seminal written report. These instructions were translated into Spanish (see the exact instructions in the Appendix) and were displayed on the computer screen earlier the experimental trials. The duration of the experimental sessions was betwixt 45 and 60 min. Although no breaks were scheduled during the experimental session, participants were instructed to work at their ain pace and allowed to take brief breaks betwixt stimuli when needed.

Results and discussion

The consummate gear up of SER ratings for the v,500 stimuli are bachelor for downloading from the journal website as supplementary materials (SpanishSER.xlsx). The file includes a column listing the 5,500 Spanish words in alphabetical order, with a matching column list their English language translations. In adjacent columns, the mean rating (SER_m) and the corresponding standard deviation (SER_sd) are provided for each word.

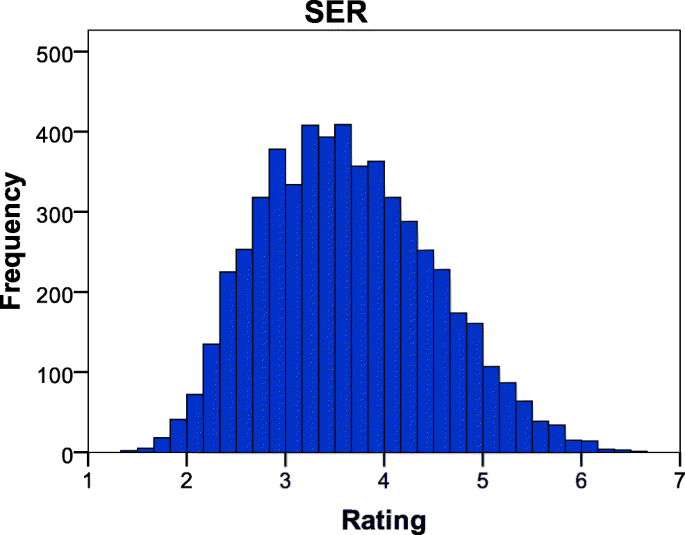

The distribution of the mean SERs was characterized by an average score of 3.63, a standard deviation of 0.86, a median of iii.57, and a range of five.07, with a minimum value of one.47 and a maximum value of vi.54. Every bit tin can be seen in Fig. 1, ratings were well distributed along the 7-point scale, with a skewness of 0.32 (SE = 0.03) and a kurtosis of – 0.35 (SE = 0.07). For completeness, descriptive statistics were calculated for the words in each role-of-spoken language category (i.e., discussion class/grammatical category), which was extracted from the EsPal database Footnote ane (Duchon, Perea, Sebastián-Gallés, Martí, & Carreiras, 2013). Very small differences were constitute betwixt the overall hateful scores of the unlike categories. These information are presented in Tabular array 1. Words pertaining to categories with less than 15 members in this report were grouped in a single category, under the proper noun Other.

Distribution of sensory experience ratings (SERs) for the v,500 words

Reliability and validity

Prior to exploring SER's relationship with other variables, we established the reliability and validity of our study. To assess interrater reliability, the intraclass correlation (ICC) was calculated (two-way random consistency model, boilerplate measures) for each ane of the 11 questionnaires. ICC values ranged from .89 to .92, with a hateful of .91, indicating a expert interrater reliability (Hallgren, 2012). Also, a mean Cronbach's blastoff of .91 (with values ranging from .89 to .92) indicated practiced internal consistency. In addition, as mentioned above, each questionnaire contained 23 words that were presented twice, making a total of 253 repeated stimuli in the study (23 words × 11 questionnaires), which allowed for analyzing intrasubject reliability. A high positive correlation (r = .969, p < .001) revealed very skillful intrasubject reliability.

The validity of the present norms was assessed in two ways. First, we translated our stimuli into English Footnote 2 and compared the ratings with the norms provided past Juhasz and Yap (2013) for a set of 2,988 shared words. The correlation was positive and meaning, although moderate (r = .435, p < .001), probably due to the fact that different meanings exist for superficially equivalent words in the two languages, and other translation issues. Withal, in a second validity assay we compared our results with the norms provided by Hinojosa, Rincón-Pérez, et al. (2016b), the only published study that has nerveless SER ratings in Spanish to appointment, and a correlation of r = .818 (p < .001) was found for a set of 471 shared words. Although translation issues are the well-nigh likely explanation for the deviation between the correlations of our norms with those from the same SER studies in English and Castilian, cross-cultural differences in SER ratings should also be considered and explored in more than detail in the futurity, since a few normative studies have plant substantial differences in normative measures as a office of culture (due east.g., Umla-Runge, Zimmer, Fu, & Wang, 2012; Yoon et al., 2004).

Relation to other psycholinguistic variables

Pearson correlation analyses were carried out to explore the correlations between SER and objective and subjective lexical descriptors, obtained from unlike bachelor sources (come across Tabular array ii). The correlations between SER and several objective variables—such as log written frequency, number of messages, number of syllables, number of homophones, number of orthographical neighbors, and number of phonological neighbors (extracted from the EsPal database; Duchon et al., 2013)—were depression. However, and interestingly in terms of language processing, a moderate negative correlation (r = – .331, p < .001) was institute between SERs and lexical decision times (from González-Nosti et al., 2014; shared n = 2,765), in that words with higher SER tended to exist processed faster. This finding replicates the results obtained in previous SER studies in other languages (Bonin et al., 2015; Juhasz & Yap, 2013; Juhasz et al., 2011). In contrast, the correlation betwixt SER and give-and-take-naming latencies (from Davies et al., 2013; shared n = 2,764), although significant, was very weak (r = .060, p = .002), and hence does not allow united states to describe firm conclusions on the human relationship betwixt these two variables.

As a way to further explore the role of SER in word recognition performance, two iv-stride hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed, with lexical conclusion and give-and-take-naming response times (RTs) as dependent variables, and a set of common predictor variables entered in successive steps, before adding SERs in the final footstep. Specifically, in Footstep i, several lexical variables were entered: 11 initial phoneme features (vowel, alveolar, palatal, velar, bilabial, dental, voiced, occlusive, nasal, fricative, and liquid), coded as 0 or 1 for each feature (obtained from Davies et al., 2013), and besides six variables related to the lexical-word-form level—namely, number of messages, number of syllables, orthographic neighborhood size, phonological neighborhood size, log written frequency (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013), and oral word frequency (from Alonso, Fernandez, & Díez, 2011). In Step ii, a measure out of the objective semantic backdrop of the words was entered—namely, semantic neighborhood density (encounter Mirman & Magnuson, 2006), based on the number of nonidiosyncratic associates with a frequency of product of >1 for the word, taken from a big Spanish free-association database (Fernandez, Díez, & Alonso, 2017; Fernandez et al., 2004). In Stride 3, two subjective measures thought to be related to semantic processing were included, namely imageability (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013) and AoA (from Alonso et al., 2016; Alonso et al., 2015). Finally, following the process of Juhasz and Yap (2013), SERs were entered in the last footstep of both analyses. As is shown in Table iii, the amount of change in the variance predicted past SERs was low merely significant for lexical decision times (ΔR 2 = .013) and nonsignificant for naming times. The same pattern of results was obtained past Juhasz et al. (2011) and Bonin et al. (2015). In dissimilarity, Juhasz and Yap (2013) establish that SER predicted a reliable, although modest, corporeality of variance in both lexical decision and naming response times. The fact that SER and other semantic variables did not significantly predict naming RTs in the present report, equally compared with the results obtained by Juhasz and Yap, could exist attributed to a very item linguistic characteristic. Specifically, Spanish, like Italian or Finnish, but dissimilar languages such equally English, has a very transparent orthography, and whatever word can be correctly named by applying basic pronunciation rules, making semantic access unnecessary in naming nigh of the words, or allowing for a combination of lexical and sublexical processes (Kwok, Cuetos, Avdyli, & Ellis, 2017).

Likewise the correlations described in a higher place, moderate correlations were constitute between SER and other subjective variables of common use in psycholinguistics. For case, SER correlated positively with imageability (r = .321, p < .001) (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013; shared northward = 3,383), and negatively with AoA (r = – .376, p < .001) (obtained from Alonso et al., 2016; Alonso et al., 2015; shared northward = iv,911). Footnote iii Thus, words with college SERs tend to be more than imageable and to exist caused earlier than depression-SER words. These results replicate the most notable design of correlations with subjective indexes constitute in previous English and French SER studies (Bonin et al., 2015; Juhasz et al., 2015; Juhasz & Yap, 2013; Juhasz et al., 2011). Importantly, the relation between SER and AoA supports the idea that concepts acquired before in life tend to be associated with sensory–perceptual experiences (Juhasz & Yap, 2013), and it is in line with grounded-cognition approaches claiming that sensorimotor experiences are essential to reaching a comprehensive understanding of what AoA represents (Thill & Twomey, 2016). Furthermore, SER also correlated positively with familiarity (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013; shared n = 3,463) (r = .381, p < .001), which is consistent with Juhasz et al.'due south (2015) results, indicating that words that evoke a greater sensory feel tend to exist more familiar. In this sense, it likewise seems that high-SER words tend to be more frequent in spoken language, every bit reflected by the correlation betwixt SER and oral frequency (r = .128, p < .001) (from Alonso et al., 2011; shared n = 4,998). The correlation with log written frequency (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013; shared n = 5,496), though, was lower (r = .067, p < .001). Additionally, in line with the correlations reported by Hinojosa, Rincón-Pérez, et al. (2016b) and Bonin et al. (2018), concreteness (from EsPal; Duchon et al., 2013; shared due north = 3,465) correlated positively with SER (r = .169, p < .001), suggesting that words that imply a high sensory experience likewise tend to denote more than concrete concepts.

Relation to perception, action and emotion variables

It has been argued that SER is an integrative semantic variable that encloses diverse individual sensorial modalities that underpin perception, activity, and emotion. To report the human relationship between SER and those three dimensions, correlational analyses were conducted between SER and different subjective psycholinguistic variables associated with perception, action, and emotion in different ways. Table 4 presents a tentative organization of relevant subjective variables into these three domains, besides as the correlation with SER in each instance. About variables had significant correlations with SERs, with larger values being observed for perceptual attributes such equally color, gustatory modality, or smell, and for emotional values such as happiness or fear.

With the aim of studying in more detail the relationship between SER and individual perceptual–sensorial modalities, we examined the correlations between SER and subjective ratings for seven dissimilar perceptual and motor attributes of object concepts—namely, color vividness, visual motion, sound intensity, smell intensity, taste pleasantness, graspability, and likelihood of pain (from Díez-Álamo, Díez, Alonso, Vargas, & Fernandez, 2017; shared n = 506), dimensions that engage the five Aristotelian sensory modalities (vision, touch, hearing, olfactory property, and gustation), in addition to a related sense, namely the likelihood that an object will crusade pain. The highest values corresponded to positive correlations between SER and color vividness (r = .419, p < .001), gustation pleasantness (r = .355, p < .001), and smell intensity (r = .296, p < .001), reflecting that high-SER words tend to elicit higher ratings particularly in these three dimensions. Interestingly, these three variables formed a statistically determined cluster in studies by Amsel et al. (2012) and by Díez-Álamo et al. (2017), every bit shown by master component analyses (PCAs) and supported past the patterns of intercorrelations among the 7 attributes. In both studies, the cluster was interpreted as a factor related to survival, described equally "locating nourishment," and included by and large objects with brilliant colors, good gustatory modality, and a potent aroma (mostly foods). Thus, the SER variable may be continued, to a large extent, to knowledge types that are almost notable in the conceptual representations of edible things (Amsel et al., 2012). It should be kept in mind, though, that the studies by Amsel et al. and Díez-Álamo et al. only included nouns denoting object concepts, so further exploration will exist needed to examine the relationship between SER and the sensory modalities for words representing other grammatical categories.

In terms of activeness, ii unlike subjective variables were taken into consideration. The first of these was graspability (the likelihood that an object can be grasped past someone with a hand, as reported in Díez-Álamo et al., 2017), which also beingness related to the sense of impact is as well regarded as an action-related dimension. Withal, the correlation between SER and graspability was not meaning (r = – .071, p = .113). The other examined action variable was the body–object interaction (BOI) index, which reflects the ease with which individuals can physically interact with an object using any part of their body (Bennett et al., 2011; Tillotson et al., 2008). Again, there was no relationship between BOI ratings (reported in Alonso et al., 2018; shared n = 750) and SER (r = – .007, p = .846). It seems, therefore, that SER does not show a clear clan with activeness variables, in contrast to its more obvious relationship with variables that address perceptual dimensions.

2 dissimilar but complementary approaches have been used to study emotion and affective language. One approach is that of dimensional models, which anticipate all human emotions every bit being based on three underlying melancholia dimensions: valence (ranging from pleasant to unpleasant), arousal (ranging from calm to excited), and authorization or control (ranging from out of control to in command) (Bradley & Lang, 1999). The dominance dimension has been shown to be less consistent across languages than valence (Redondo et al., 2007; Warriner, Kuperman, & Brysbaert, 2013), a weaker predictor of variance than valence and arousal (Bradley & Lang, 1994), and to be highly correlated with valence (Warriner et al., 2013). As a result, most mod studies in a variety of domains (such as language, memory, and emotion) usually exercise non include potency in their models (e.g., Ferré, Guasch, Moldovan, & Sánchez-Casas, 2012; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004; Kuperman, Estes, Brysbaert, & Warriner, 2014; Stadthagen-González, Imbault, Pérez Sánchez, & Brysbaert, 2017b). Thus, for the purpose of this study, we besides decided to focus on the valence and arousal dimensions. Equally we explained in the Method section, nosotros initially selected i,512 words with known affective norms from Redondo et al. (2005, 2007). Yet, during the final stages in the preparation of the present report, a much larger normative study with norms of valence and arousal was published (Stadthagen-González, Imbault, et al., 2017b), including all the words in Redondo et al. (2007) and over 95% of the words in Redondo et al. (2005). Consequently, to maximize the number of shared items with our study, we decided to use the norms provided by Stadhagen-González, Imbault, et al. to calculate the correlations between our SER ratings and valence and arousal for a total of 4,421 shared words. A positive significant correlation was constitute between SER and valence (r = .105, p < .001), reflecting a trend for high-SER words to be judged as more positive. A larger positive correlation was found betwixt SER and arousal (r = .254, p < .001), indicating that, as was previously found by Hinojosa, Rincón-Pérez, et al. (2016b), words with higher SERs were more probable to be judged every bit being relatively more arousing than words with lower SERs.

An alternative approach for studying emotion, supported by research in facial expressions (Ekman, 1993, 1999), is based on the being of a limited number of discrete basic emotions. Although there is no consummate consensus regarding the number of discrete basic emotions, 5 of them (happiness, disgust, anger, fright, and sadness) have received stronger support (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987; Power & Dalgleish, 1997). To further explore the role of SER in the emotional domain, we examined the correlations between SER and those v discrete emotions, using subjective emotional ratings for a set of 4,498 shared items obtained from a combination of three normative studies (Ferré, Guasch, Martínez-García, Fraga, & Hinojosa, 2017; Hinojosa, Martínez-García, et al., 2016a; Stadthagen-González, Ferré, Pérez-Sánchez, Imbault, & Hinojosa, 2017a). SER correlated significantly with the 5 discrete emotions, and all the correlations were positive (see Tabular array iv). This is consistent with the results observed in Hinojosa, Rincón-Pérez, et al.'due south (2016b) study. The highest correlation was found between SER and happiness (r = .361, p < .001), indicating that words with a higher SER tend to denote more pleasant concepts.

Boosted regression analyses

Finally, to explore more than deeply the nature of SER ratings, ii hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with SER as the dependent variable. The first assay included the objective and subjective lexical and semantic variables used in the previously described regression analyses on lexical decision and naming times every bit successive predictors of SER ratings—excluding the xi initial phoneme features—for the set of 2,272 words that had all the scores bachelor. A 2d analysis also included the perception, action, and emotion variables (listed in Table 4) in successive steps, just in this example for a reduced set up of 318 words, since non all scores were bachelor for the normed words. Tabular array 5 shows the results of both analyses. Importantly, the nine lexical and semantic predictor variables only deemed for 11.3% of the variance in SERs (15% in the reduced-set analysis), with the inbound of subjective semantic variables in the model producing the greater increase in the explained variance. However, the greatest increments of explained variance were produced by inbound perception (ΔR 2 = .xviii), action (ΔR 2 = .05), and emotional (ΔR 2 = .22) variables, which together raised R 2 upward to .59.

Conclusion

In the present report, we provide SERs for a set of 5,500 Spanish words, which constitutes, to date, the largest set of norms for SER in Spanish language. Reliability and validity analyses showed that the norms provide adequate estimators of SER for this large fix of words. In addition, with the exception of iv entries, all of the words from the present study are contained in the EsPal database (Duchon et al., 2013). As a event, a very large amount of lexical information is bachelor for all the words, including lemma information, give-and-take written frequency, and orthographic and phonological characteristics, every bit well every bit different subjective ratings for a subset of over 3,300 words. Additionally, virtually v,000 of the words are also described in oral frequency norms (Alonso et al., 2011), and AoA norms (Alonso et al., 2016; Alonso et al., 2015), and over 4,400 of the words are nowadays in affective norms databases, including valence and arousal norms (Stadthagen-González, Imbault, et al., 2017b) and ratings for five discrete emotions (Ferré et al., 2017; Hinojosa, Martínez-García, et al., 2016a; Stadthagen-González, Ferré, et al., 2017a). Finally, lexical decision (González-Nosti et al., 2014) and naming response times (Davies et al., 2013) are bachelor for approximately half of the words, and additional indexes of psycholinguistic interest can be constitute for smaller subsets of words. From a methodological point of view, the availability of SERs for a big gear up of words that are well characterized in many other dimensions has the potential to be of utilize to researchers interested in designing studies of conceptual representation, semantic retentiveness, processing of affective language and other related issues with samples of Castilian-speaking participants. The norms also take the potential to be useful in studies on different aspects of bilingualism, and they might provide indications for future enquiry efforts on cross-cultural issues. And from a broader theoretical perspective, our results are important for understanding the nature of the construct captured by SERs. Finally, the materials and the data about the relation betwixt SER and other variables might be helpful for the strengthening and development of new lines of research in psychology, particularly recent encephalon-inspired proposals about conceptual representation and conceptual processing that consider the demand to integrate perceptual, motor and emotional information (due east.g., Folder et al., 2016; Glenberg, 2015; Kiefer & Barsalou, 2013; Lambon Ralph, Jefferies, Patterson, & Rogers, 2017).

Notes

-

The office-of-voice communication categories for four words that were not contained in EsPal, also every bit their numbers of letters and syllables, were assigned by the showtime writer.

-

The 5,500 Spanish words were initially translated into English using Google Translate. In a second step, all the resulting translations were revised by ii of the authors (A.M.D.-Á. and D.Z.W.), who are expert in both Spanish and English language.

-

In the cases that a discussion was nowadays in both studies, the boilerplate of the two numbers was used.

References

-

Alonso, Thou. A., Díez, E., Díez-Álamo, A. M., & Fernandez, A. (2018). Torso–object interaction ratings for 750 Spanish words. Applied Psycholinguistics.

-

Alonso, Yard. A., Díez, E., & Fernandez, A. (2016). Subjective age-of-acquisition norms for iv,640 verbs in Spanish. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 48, 1337–1342. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0675-z

-

Alonso, M. A., Fernandez, A., & Díez, E. (2011). Oral frequency norms for 67,979 Spanish words. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0062-3

-

Alonso, One thousand. A., Fernandez, A., & Díez, Due east. (2015). Subjective age-of-conquering norms for 7,039 Spanish words. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0454-2

-

Amsel, B. D., Urbach, T. P., & Kutas, One thousand. (2012). Perceptual and motor aspect ratings for 559 object concepts. Behavior Research Methods, 44, 1028–1041. https://doi.org/ten.3758/s13428-012-0215-z

-

Barca, L., Burani, C., & Arduino, L. S. (2002). Word naming times and psycholinguistic norms for Italian nouns. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 34, 424–434. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195471

-

Barsalou, 50. Due west. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 577–660. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X99532147

-

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded knowledge. Almanac Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

-

Barsalou, Fifty. W., Simmons, W. Thousand., Barbey, A. K., & Wilson, C. D. (2003). Grounding conceptual knowledge in modality-specific systems. Trends in Cerebral Sciences, vii, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(02)00029-3

-

Bennett, S. D. R., Burnett, A. N., Siakaluk, P. D., & Pexman, P. Yard. (2011). Imageability and trunk–object interaction ratings for 599 multisyllabic nouns. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 1100–1109. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0117-5

-

Binder, J. R., Conant, Fifty. 50., Humphries, C. J., Fernandino, 50., Simons, S. B., Aguilar, M., & Desai, R. H. (2016). Toward a encephalon-based componential semantic representation. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 33, 130–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643294.2016.1147426

-

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Aubert, 50., Malardier, N., Niedenthal, P., & Capelle-Toczek, Chiliad.-C. (2003). Normes de concrétude, de valeur d'imagerie, de fréquence subjective et de valence émotionnelle pour 866 mots. L'année Psychologique, 103, 655–694.

-

Bonin, P., Méot, A., & Bugaiska, A. (2018). Concreteness norms for ane,659 French words: Relationships with other psycholinguistic variables and word recognition times. Behavior Research Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1014-y

-

Bonin, P., Méot, A., Ferrand, 50., & Bugaïska, A. (2015). Sensory experience ratings (SERs) for i,659 French words: Relationships with other psycholinguistic variables and visual word recognition. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 47, 813–825. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-014-0503-ten

-

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-cess manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Beliefs Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

-

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affective norms for English language words (Afresh): Instruction manual and melancholia ratings. Gainesville, FL: Center for Research in Psychophysiology, Academy of Florida.

-

Davies, R., Barbón, A., & Cuetos, F. (2013). Lexical and semantic age-of-acquisition effects on word naming in Spanish. Retentivity & Cognition, 41, 297–311. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0263-8

-

Díez-Álamo, A. M., Díez, E., Alonso, M. A., Vargas, C. A., & Fernandez, A. (2017). Normative ratings for perceptual and motor attributes of 750 object concepts in Spanish. Beliefs Research Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0970-y

-

Duchon, A., Perea, Grand., Sebastián-Gallés, N., Martí, A., & Carreiras, M. (2013). EsPal: One-stop shopping for Castilian word properties. Beliefs Research Methods, 45, 1246–1258. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-013-0326-one

-

Ekman, P. (1993). Facial expression and emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.four.384

-

Ekman, P. (1999). Facial expressions. In T. Dalgleish & Chiliad. J. Ability (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 301–320). New York, NY: Wiley.

-

Fernandez, A., Díez, E., & Alonso, M. A. (2017). Normas de Asociación libre en castellano de la Universidad de Salamanca [online database]. Retrieved from campus.usal.es/gimc/nalc

-

Fernandez, A., Díez, Due east., Alonso, M. A., & Beato, One thousand. S. (2004). Free-association norms for the Castilian names of the Snodgrass and Vanderwart pictures. Beliefs Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 577–583. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195604

-

Ferré, P., Guasch, Thousand., Martínez-García, Northward., Fraga, I., & Hinojosa, J. A. (2017). Moved by words: Affective ratings for a set of ii,266 Castilian words in five discrete emotion categories. Behavior Research Methods, 49, 1082–1094. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-016-0768-3

-

Ferré, P., Guasch, Grand., Moldovan, C., & Sánchez-Casas, R. (2012). Affective norms for 380 Spanish words belonging to three different semantic categories. Behavior Research Methods, 44, 395–403. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0165-x

-

Glenberg, A. M. (2011). How reading comprehension is embodied and why that matters. International Electronic Journal of Unproblematic Instruction, 4, 5–xviii.

-

Glenberg, A. M. (2015). Few believe the globe is flat: How embodiment is changing the scientific understanding of cognition. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/cep0000056

-

Glenberg, A. M., & Kaschak, M. P. (2002). Grounding language in activeness. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 558–565. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196313

-

González-Nosti, G., Barbón, A., Rodríguez-Ferreiro, J., & Cuetos, F. (2014). Furnishings of the psycholinguistic variables on the lexical determination job in Spanish: A written report with two,765 words. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 517–525. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0383-5

-

Hallgren, K. A. (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8, 23–34. https://doi.org/ten.20982/tqmp.08.ane.p023

-

Hinojosa, J. A., Martínez-García, N., Villalba-García, C., Fernández-Folgueiras, U., Sánchez-Carmona, A., Pozo, M. A., & Montoro, P. R. (2016a). Affective norms of 875 Spanish words for five discrete emotional categories and two emotional dimensions. Behavior Enquiry Methods, 48, 272–284. https://doi.org/ten.3758/s13428-015-0572-five

-

Hinojosa, J. A., Rincón-Pérez, I., Romero-Ferreiro, K. V., Martínez-García, Northward., Villalba-García, C., Montoro, P. R., & Pozo, Grand. A. (2016b). The Madrid Melancholia Database for Spanish (MADS): Ratings of authorization, familiarity, subjective age of acquisition and sensory experience. PLoS I, 11, e0155866. https://doi.org/ten.1371/journal.pone.0155866

-

Hirschfeld, K., Bien, H., de Vries, M., Lüttmann, H., & Schwall, J. (2010). Open-source software to conduct online rating studies. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 542–546. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.two.542

-

Juhasz, B. J., Lai, Y.-H., & Woodcock, Thou. L. (2015). A database of 629 English chemical compound words: Ratings of familiarity, lexeme meaning authority, semantic transparency, age of acquisition, imageability, and sensory experience. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 47, 1004–1019. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0523-vi

-

Juhasz, B. J., & Yap, Thou. J. (2013). Sensory experience ratings for over 5,000 mono- and disyllabic words. Behavior Research Methods, 45, 160–168. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0242-9

-

Juhasz, B. J., Yap, M. J., Dicke, J., Taylor, S. C., & Gullick, M. 1000. (2011). Tangible words are recognized faster: The grounding of significant in sensory and perceptual systems. Quarterly Periodical of Experimental Psychology, 64, 1683–1691. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2011.605150

-

Kaschak, M. P., Madden, C. J., Therriault, D. J., Yaxley, R. H., Aveyard, One thousand., Blanchard, A. A., & Zwaan, R. A. (2005). Perception of motion affects language processing. Cognition, 94, B79–B89. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.cognition.2004.06.005

-

Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2004). Two routes to emotional memory: Distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 3310–3315. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0306408101

-

Kiefer, Thousand., & Barsalou, 50. W. (2013). Grounding the human conceptual system in perception, activity, and internal states. In Westward. Prinz, M. Beisert, & A. Herwig (Eds.), Activity scientific discipline: Foundations of an emerging subject area (pp. 381–407). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

-

Kousta, Due south.-T., Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D. P., Andrews, M., & Del Campo, E. (2011). The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140, 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021446

-

Kuperman, V. (2013). Accentuate the positive: Semantic access in English language compounds. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00203

-

Kuperman, Five., Estes, Z., Brysbaert, M., & Warriner, A. B. (2014). Emotion and language: Valence and arousal impact word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 1065–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035669

-

Kwok, R. G. W., Cuetos, F., Avdyli, R., & Ellis, A. W. (2017). Reading and lexicalization in opaque and transparent orthographies: Discussion naming and discussion learning in English and Spanish. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70, 2105–2129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1223705

-

Lambon Ralph, K. A., Jefferies, East., Patterson, 1000., & Rogers, T. T. (2017). The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, eighteen, 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.150

-

Liu, Y., Shu, H., & Li, P. (2007). Word naming and psycholinguistic norms: Chinese. Beliefs Research Methods, 39, 192–198. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193147

-

Lynott, D., & Connell, L. (2013). Modality exclusivity norms for 400 nouns: The human relationship between perceptual experience and surface word form. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 45, 516–526. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0267-0

-

McRae, K., Cree, G. S., Seidenberg, G. S., & McNorgan, C. (2005). Semantic feature production norms for a large set of living and nonliving things. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 37, 547–559. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192726

-

Medler, D. A., Arnoldussen, A., Binder, J. R., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2005). The wisconsin perceptual attribute ratings database. Retrieved from world wide web.neuro.mcw.edu/ratings/

-

Mirman, D., & Magnuson, J. Southward. (2006). The touch of semantic neighborhood density on semantic access. In R. Dominicus & N. Miyake (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th Almanac Conference of the Cerebral Scientific discipline Society (pp. 1823–1828). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

-

Oatley, Thousand., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1987). Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 29–fifty. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699938708408362

-

Pérez, K. A., Campoy, Chiliad., & Navalón, C. (2001). Índice de estudios normativos en idioma español. Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada, 6, 85–105.

-

Ability, M., & Dalgleish, T. (1997). Noesis and emotion: From society to disorder. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

-

Proctor, R. W., & Vu, K.-P. L. (1999). Index of norms and ratings published in the Psychonomic Society journals. Beliefs Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31, 659–667. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200742

-

Redondo, J., Fraga, I., Comesaña, Thousand., & Perea, Yard. (2005). Estudio normativo del valor afectivo de 478 palabras españolas. Psicológica, 26, 317–326.

-

Redondo, J., Fraga, I., Padrón, I., & Comesaña, M. (2007). The Spanish adaptation of ANEW (Melancholia Norms for English Words). Beliefs Research Methods, 39, 600–605. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193031

-

Sanfeliu, M. C., & Fernandez, A. (1996). A gear up of 254 Snodgrass–Vanderwart pictures standardized for Spanish: Norms for name agreement, paradigm understanding, familiarity, and visual complexity. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 537–555. https://doi.org/ten.3758/BF03200541

-

Snodgrass, J. G., & Vanderwart, 1000. (1980). A standardized set of 260 pictures: Norms for name agreement, prototype agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Man Learning and Retentivity, 6, 174–215. https://doi.org/x.1037/0278-7393.6.2.174

-

Stadthagen-González, H., Ferré, P., Pérez-Sánchez, M. A., Imbault, C., & Hinojosa, J. A. (2017a). Norms for 10,491 Spanish words for five discrete emotions: Happiness, disgust, acrimony, fright, and sadness. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-017-0962-y

-

Stadthagen-González, H., Imbault, C., Pérez Sánchez, M. A., & Brysbaert, M. (2017b). Norms of valence and arousal for xiv,031 Spanish words. Behavior Research Methods, 49, 111–123. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-015-0700-2

-

Thill, S., & Twomey, Grand. E. (2016). What'southward on the inside counts: A grounded account of concept acquisition and development. Frontiers in Psychology, seven, 402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00402

-

Tillotson, S. M., Siakaluk, P. D., & Pexman, P. Thou. (2008). Body–object interaction ratings for 1,618 monosyllabic nouns. Behavior Research Methods, xl, 1075–1078. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.4.1075

-

Umla-Runge, K., Zimmer, H. D., Fu, X., & Wang, Fifty. (2012). An activeness video clip database rated for familiarity in Communist china and Germany. Behavior Inquiry Methods, 44, 946–953. https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-012-0189-x

-

Vaughan, J. (2004). Editorial: A Web-based annal of norms, stimuli, and data. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195583

-

Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). Norms of valence, arousal, and authorization for 13,915 English language lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 45, 1191–1207. https://doi.org/ten.3758/s13428-012-0314-x

-

Yoon, C., Feinberg, F., Luo, T., Hedden, T., Gutchess, A. H., Chen, H.-Y. M., … Park, D. C. (2004). A cantankerous-culturally standardized fix of pictures for younger and older adults: American and Chinese norms for name agreement, concept agreement, and familiarity. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 639–649. https://doi.org/x.3758/BF03206545

Author note

The authors were supported past research grants awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Grants PSI2013-42872-P and PSI2017-82748-P). Boosted support came from a predoctoral grant from the University of Salamanca and Banco Santander to A.Grand.D.-Á. (Grant 463A.B.01, 2013), and from a research grant from Programme Propio de Investigación de la Universidad de La Laguna to M.A.A. (Grant 2017/0001035). The raw data from this study are bachelor at the Open Scientific discipline Framework (https://osf.io/52fah/).

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix: Rating instructions

Appendix: Rating instructions

"A continuación se te presentará una serie larga de palabras. Por favor, lee y considera cada palabra basándote en el grado de experiencia sensorial que cada una evoca en ti. Por experiencia sensorial, entendemos una sensación real (gusto, tacto, vista, sonido, u olfato) que experimentas al leer la palabra. Por favor, evalúa cada palabra en una escala del i al seven, donde 1 significa que la palabra no evoca ninguna experiencia sensorial en ti, 4 significa que la palabra evoca una experiencia sensorial moderada, y vii significa que la palabra evoca una experiencia sensorial fuerte. No hay respuestas correctas o incorrectas. Estamos interesados en tu experiencia sensorial personal con estas palabras. Puedes indicar tu respuesta para cada palabra señalando el número que elijas en la escala."

Rights and permissions

Well-nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Díez-Álamo, A.M., Díez, E., Wojcik, D.Z. et al. Sensory experience ratings for v,500 Spanish words. Behav Res 51, 1205–1215 (2019). https://doi.org/x.3758/s13428-018-1057-0

-

Published:

-

Effect Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1057-0

Keywords

- Sensory experience ratings (SERs)

- Spanish norms

- Grounded cognition

- Perception

- Action

- Emotion

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13428-018-1057-0

0 Response to "A Sensory Experience That Two or More Persons Can Experience Objectively Is Known as:"

Post a Comment